NEHH@20

Introduction

In 2025, the Congregational Library & Archives is commemorating the 20th anniversary of the New England’s Hidden Histories (NEHH) project. Over the past twenty years, NEHH has contributed to new narratives about the past and understandings of community histories. The thirteen essays in this exhibition feature stories that exemplify the value of turning to primary sources to re-examine our understanding of early New England communities.

NEHH began at the Congregational Library & Archives (CLA) in 2005 as a small-scale digitization project, in partnership with the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale, to preserve some of the oldest manuscript Congregational church records in New England.

The first several years of the NEHH project focused on locating, rescuing, and preserving rare seventeenth- and eighteenth-century church records from Massachusetts towns. One remarkable early find came in 2007, with the unearthing of the Phillips Diary, a five-hundred-page volume of church records written by the pastor in Rowley, Massachusetts, beginning in the 1660s. By 2010, the CLA’s Executive Director, Dr. Peggy Bendroth, and the library staff began making colonial-era church records available online, beginning with the First Congregational Church of Natick, Massachusetts. By early 2014, records from 17 churches and individuals were online, and more were added on a regular basis. In 2016, records from 34 churches and individuals were available on the NEHH website. Today, the NEHH project has grown into a digital archive with 130,000 digital images and over 26,000 pages of transcription, representing 160 historic New England churches and over 100 collections of personal papers.

Working in partnership with libraries, archives, museums, churches, and other cultural institutions, the project team has uncovered valuable, and too often overlooked, firsthand accounts that preserve the voices of early New Englanders. Dr. Harold Field Worthley (CLA Executive Director 1977-2003) laid vital groundwork for NEHH’s commitment to gathering and preserving church records. His 1970 publication commonly known as the Worthley Inventory, describes the known Massachusetts Congregational church records and is still an invaluable resource. NEHH expanded in 2015 when Dr. James F. Cooper, Jr., who had already spent summers searching for missing and rare church records, became the full-time Director of NEHH and Helen K. Gelinas became Transcription Director. NEHH has also been sustained and enriched through the efforts of volunteer transcribers, whose dedicated work to unravel the intricacies of early modern handwriting has made these records more accessible to the public.

NEHH@20: Re-Examining Stories from New England Communities showcases the work of scholars, church historians, and transcribers who have contributed to the project and uncovered new histories in the process. The exhibition explores important research that has come from this archive and its impact on community histories of New England.

The essays and digitalized items that follow are organized chronologically, starting with Richard Mather’s c.1651 An Answere of the Elders to certayne doubts, and concluding with the records of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society from the 1830s. They highlight the value of recovering stories that broaden our understanding of New England history. Many of the people in these documents do not appear anywhere else in the historical record, exemplifying why Congregational history is New England history. Records in the NEHH digital archive reveal much about communities and individuals beyond mere church histories. Several of these essays focus on women’s voices, highlighting this important source material. NEHH includes what may be the largest concentration of eighteenth-century writings by New England women ever assembled. Four of the essays focus on the complex relationships of Black and Indigenous peoples to Christianity and Congregational churches’ roles in maintaining slavery and settler colonialism.

Another important theme of these essays is the connection between Congregationalism and politics, including debates about church governance, direct advocacy for the Massachusetts royal charter, support for the American Revolution, and the nineteenth-century antislavery movement. The items in this exhibit, and the NEHH digital archive as a whole, reveal not only personal struggles, strained and broken relationships, and inequalities, but also spiritual fulfillment and joy, reconciliation and compromise, and Congregationalists’ pursuit of justice.

NEHH@20: Re-examining Stories from New England Communities shows the significance of NEHH as a digital history project. The body of collaborative work that has emerged from twenty years of research (in this exhibition and elsewhere) reveals the ongoing relevance of this work.

The items in this exhibition are drawn from the collections of the Congregational Library & Archives and partner institutions in the New England’s Hidden Histories project.

By Richard Boles and Tricia Peone, co-curators

To navigate the exhibition, use the arrows at the bottom or top of the page (depending on your device). Hover over the icons in the center of the page to switch to full screen, change the width of the panels, view captions, or follow links to related resources. Note that the viewing experience may change depending on your browser.

Richard Mather, An Answere of the Elders to certayne doubts, circa 1651

For the puritans of seventeenth-century Massachusetts, the central text outlining Congregationalism was the Cambridge Platform, written from 1648-1651. Just as the Declaration of Independence emerged from the work of a committee, yet largely through Thomas Jefferson’s pen, the Cambridge Platform was the work of Richard Mather (1596-1669). Among the first generation of colonists, Mather was a respected Massachusetts cleric and patriarch of the now-legendary Mather family. Before the Cambridge Synod of 1646-48, he wrote a draft of the Cambridge Platform. As the Cambridge Platform worked its way across the colony, the General Court encouraged churches and churchgoers to submit questions, concerns, and objections about the work. The General Court forwarded the 71 questions to the Synod Elders, who in turn tasked a committee led by Mather to answer the objections and issue a formal written defense for the Cambridge Platform. The result was “An Answere of the Elders to Certayne doubts and objections agt sundry passages in the Platforme of Discipline,” produced by Mather’s committee and written in his hand. This text is one of dozens of important Mather family documents that the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) has made accessible through digitization and transcription.

For the puritans of seventeenth-century Massachusetts, the central text outlining Congregationalism was the Cambridge Platform, written from 1648-1651. Just as the Declaration of Independence emerged from the work of a committee, yet largely through Thomas Jefferson’s pen, the Cambridge Platform was the work of Richard Mather (1596-1669). Among the first generation of colonists, Mather was a respected Massachusetts cleric and patriarch of the now-legendary Mather family. Before the Cambridge Synod of 1646-48, he wrote a draft of the Cambridge Platform. As the Cambridge Platform worked its way across the colony, the General Court encouraged churches and churchgoers to submit questions, concerns, and objections about the work. The General Court forwarded the 71 questions to the Synod Elders, who in turn tasked a committee led by Mather to answer the objections and issue a formal written defense for the Cambridge Platform. The result was “An Answere of the Elders to Certayne doubts and objections agt sundry passages in the Platforme of Discipline,” produced by Mather’s committee and written in his hand. This text is one of dozens of important Mather family documents that the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) has made accessible through digitization and transcription.

“An Answere of the Elders” exhibits the method that New England clergy employed to justify the Congregational church structure (and their authority within it) against the Presbyterians, whose alternative was by the end of the 1640s ascendant, particularly in England. It also addressed the puritan Independents who saw in the Cambridge Platform an illegitimate clerical assertion of authority. In defending the Synod’s work, the “Answere to the Elders” provides a snapshot of the relationship between the New England Clergy and the Presbyterians and Reformed Anticlericals in puritan New England’s churches. The document depicts a strained and terse relationship with Presbyterians and Presbyterianism, while also demonstrating the New England clergy’s elaborate attempts to persuade New England churches, and the Anticlericals within them, to accept the Cambridge Platform.

By Samuel Jennings, NEHH transcriber, Ph.D. candidate, Oklahoma State University

View “An Answere of the Elders to certayne doubts” here.

Above: Portait of Richard Mather by Johannes Foster, c. 1665. Congregational Library & Archives.

Letter from Cotton Mather to Increase Mather, 1690 May 17

On May 17, 1690, a twenty-seven-year-old Cotton Mather (1663-1728) wrote a letter to his father, Increase Mather, pleading with him to return to New England. He was distressed by Increase’s four-year absence from Boston, a consequence of the 1684 revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Charter. In the midst of various difficulties at home, Increase was on a mission in England to advocate for the Charter’s restoration. Though Cotton’s letter is only two pages long, it clearly shows great anguish at his father’s absence. His diary at the time is similarly expressive. In one diary entry, speaking of his father’s departure, he wrote, “This Day, was with mee, a Day of singular Distress....I confessed my Unworthiness of all Mercies; and especially such a Mercy, as the Enjoyment of such a Father, as mine.” Similarly, in his letter, he spoke of being sorry “for ye Country, ye Colledge, your own church...your Family” and “myself, who am Left alone, in ye midst of more Cares, Fears, Anxieties, than, I beleeve, any one person in these Territories.”

On May 17, 1690, a twenty-seven-year-old Cotton Mather (1663-1728) wrote a letter to his father, Increase Mather, pleading with him to return to New England. He was distressed by Increase’s four-year absence from Boston, a consequence of the 1684 revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Charter. In the midst of various difficulties at home, Increase was on a mission in England to advocate for the Charter’s restoration. Though Cotton’s letter is only two pages long, it clearly shows great anguish at his father’s absence. His diary at the time is similarly expressive. In one diary entry, speaking of his father’s departure, he wrote, “This Day, was with mee, a Day of singular Distress....I confessed my Unworthiness of all Mercies; and especially such a Mercy, as the Enjoyment of such a Father, as mine.” Similarly, in his letter, he spoke of being sorry “for ye Country, ye Colledge, your own church...your Family” and “myself, who am Left alone, in ye midst of more Cares, Fears, Anxieties, than, I beleeve, any one person in these Territories.”

Despite his letter, it would be another two years before Increase returned from England. Cotton, in his diary for 1692, records, “On 14d 3m Satureday-Evening. My Father arrived unto mee....Oh! what shall I render to ye Lord, for all His Benefits!” And, on the matter of the new Massachusetts Charter, which put in place a provincial governor appointed by the King, he also recorded his initial impression: “Wee have not or former Charter, but wee have a Better in ye Room of it. One which much better Suits or circumstances....The Governour of ye province is not my Enemy, but one whom I Baptised, namely Sir William Phips, and one of my own Flock, & one of my dearest Friends.”

These documents, and others like them, provide intimate access to the thoughts and actions of Mather family members, surely one of the most famous and studied puritan dynasties. The digitization, and especially corresponding transcriptions, produced by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH), has made the Mathers more accessible to modern audiences.

By Barbara Worthley, NEHH Transcriber

View Cotton Mather’s letter to his father here.

For more information, see the Cotton Mather bibliography.

Above: Portrait of Cotton Mather by Peter Pelham, 1728. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ebenezer Turell account of a witchcraft case, 1728

In 1720, when Elizabeth, the eldest of a family with three children in Littleton, Massachusetts, began exhibiting unusual behaviors, such as falling into trances, seeing specters, and exhibiting pinch marks on her body, a dreaded fear arose in the community that the “Evil Hand” was upon her. When her younger sister began to evince the same symptoms, and both girls terrified their parents by calling out from roofs or nearly drowning in ponds to which they had been transported by a power in the air, it was clear that the plague of witchcraft that had upended Salem nearly thirty years earlier had returned. Even the youngest child, only five years old, showed signs of affliction. But when Mrs. D., a neighbor whom Elizabeth claimed was her tormentor suddenly died, a wave of abject terror gripped the community.

In 1720, when Elizabeth, the eldest of a family with three children in Littleton, Massachusetts, began exhibiting unusual behaviors, such as falling into trances, seeing specters, and exhibiting pinch marks on her body, a dreaded fear arose in the community that the “Evil Hand” was upon her. When her younger sister began to evince the same symptoms, and both girls terrified their parents by calling out from roofs or nearly drowning in ponds to which they had been transported by a power in the air, it was clear that the plague of witchcraft that had upended Salem nearly thirty years earlier had returned. Even the youngest child, only five years old, showed signs of affliction. But when Mrs. D., a neighbor whom Elizabeth claimed was her tormentor suddenly died, a wave of abject terror gripped the community.

Roughly eight years later, in Medford, Massachusetts, when the young pastor Ebenezer Turrell (1702-1778) was approached by Elizabeth seeking admission to his church, he little dreamed of the evil secret she carried in her heart. It was not until after she heard a sermon that he happened to preach on the sin of lying and the damnation of liars, that the young woman again approached his office and made a stunning confession.

Rev. Turrell’s account details deception and susceptibility that he alleged by “strict examination might have been detected” as nothing more than “the contrivance of evil… by the children of men.” In six short chapters, he recounted the dangerous events and included instruction he believed would put the final word on dealing with witchcraft in New England. In contrast to the results at Salem in 1692, his admonishment to his parishioners, written ironically in the year of Cotton Mather’s death, is a scathing rebuke to the Littleton community and others like it. In divulging the events based on Elizabeth’s confession, Turrell placed the blame squarely on the credulity of undiscerning believers. His powerful words served as an attempt to bring a generation of colonists “out of darkness and into the Light.”

In a parallel way, the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) has illuminated many previously unknown narratives that clarify relationships, conflicts, and lived religious practices across communities.

By Helen K. Gelinas, NEHH Transcription Director

View Ebenezer Turrell’s account of a witchcraft case here.

Above: Howard Pyle, "The Trial of a Witch," Harper’s New Monthly Magazine vol. LXXXVI (1893).

Hassanamisco church book, 1731-1774, Church of Christ in Grafton, Massachusetts

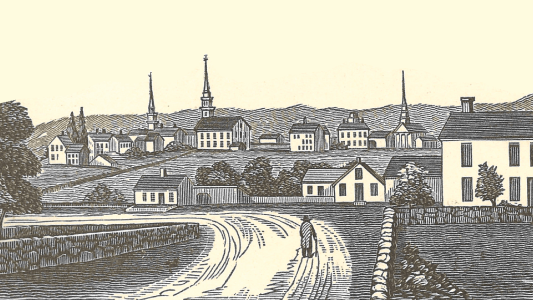

Ezekiel Cole (c. 1730-c. 1778), a Nipmuc Congregationalist in Hassanamesit/Grafton, is known only as a very minor footnote to the story of English minister Solomon Prentice. The brief church record seen here, written on February 13, 1744, brings Ezekiel Cole up and out of that footnote.

Ezekiel Cole (c. 1730-c. 1778), a Nipmuc Congregationalist in Hassanamesit/Grafton, is known only as a very minor footnote to the story of English minister Solomon Prentice. The brief church record seen here, written on February 13, 1744, brings Ezekiel Cole up and out of that footnote.

Ezekiel became a full member of the church in Hassanamesit/Grafton on February 17, 1742/3, when he was about 21 years old. Almost exactly one year later, he appears in the record here, in which “Brother Ezekiel Cole came before the Church & acknowledged he had been rash & unchristian, in charging ye Pastor with Preaching Damnable Doctrine and said he was Sorry there for, and ask’d forgiveness of Pastor & Chh, who Accordingly manifested their forgiveness.”

This church record was somehow cherry-picked by nineteenth-century Grafton town historian Frederick Clifton Pierce to function as a humorous anecdote about a disruptive “Indian.” Later historians, without access to the entire church record book, repeated this snippet, and the story of the Indigenous man who challenged the orthodox minister, until the assumption that Ezekiel Cole was an agent of chaos during the Great Awakening was firmly established in the history of the town.

But the full church record book tells a different story: Ezekiel Cole’s charge that minister Solomon Prentice preached “damnable doctrine” was eventually proven true, and Ezekiel played a dynamic role in the three-year effort to expose Solomon Prentice, who was dismissed in 1747. Ezekiel’s 1744 challenge, then, was the first warning against the minister’s theology, and the church record describes in detail how Ezekiel sought to rally the orthodox faithful through lay preaching and exhorting. Ezekiel was no outsider to Congregationalism, but a strong and authentic defender of the faith he grew up in.

How many other stories like Ezekiel Cole’s are hidden from the official history of our nation in the long-lost church records recovered by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH)?

By Lori Rogers-Stokes, NEHH contributing editor

View the Hassanamesit/Grafton church records here.

Above: "View of Grafton As It Was in 1839" from Frederick Clifton Pierce, History of Grafton (Worcester: Chas. Hamilton, 1879).

Mary Tilden disciplinary case records, 1732-1733

Many marriages were recorded for posterity in early New England church records. These disciplinary case records describe the dissolution of Mary Tilden’s (c. 1692-c. 1734) marriage. She left her husband, Stephen, in Lebanon, Connecticut in 1733. Records of this unusual case survive because a Congregational church committee was appointed to look into the matter. The committee heard testimony, solicited witnesses, and then instructed Mary Tilden to move back in with her husband and forgive him. Although the records contain intimate details of a marriage, they were created for the minister and committee. They were collected into the church’s records, and nearly three centuries later, digitized and transcribed by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH). They provide a rare opportunity to read an eighteenth-century woman’s own words and feelings about her marriage.

Many marriages were recorded for posterity in early New England church records. These disciplinary case records describe the dissolution of Mary Tilden’s (c. 1692-c. 1734) marriage. She left her husband, Stephen, in Lebanon, Connecticut in 1733. Records of this unusual case survive because a Congregational church committee was appointed to look into the matter. The committee heard testimony, solicited witnesses, and then instructed Mary Tilden to move back in with her husband and forgive him. Although the records contain intimate details of a marriage, they were created for the minister and committee. They were collected into the church’s records, and nearly three centuries later, digitized and transcribed by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH). They provide a rare opportunity to read an eighteenth-century woman’s own words and feelings about her marriage.

The church committee’s records include Mary’s explanation of why she left her husband of over fifteen years and resisted reconciliation. Two of her children had recently died, and in her grief, she had stopped eating. To make matters worse, her husband had “committed the sin of fornication” with a woman named Sarah Ellis. Mary told the committee that she feared for her sexual health–Stephen often traveled, and his temptation to sin caused her to fear that “I shall have sum distemper brought home to me.” Worse still, a witness offered testimony that Stephen was violent toward their children and to an enslaved person in their household. The witness also remarked of Stephen that “I thought he had ye least tenderness yt I ever see in any man in my life.”

In a letter addressed to her husband, Mary asks for his forgiveness but notes that the committee has told her that “it is just and reasonable that you should confess to me your faults, and harsh treatment of me and ask my forgiveness thereof.” Stephen apparently did not agree.

Several months later, Rev. Solomon Williams (1700-1776) wrote to Mary, informing her that her husband had appeared at a parish meeting and announced that he believed she should return to him. The committee voted that Mary should present herself the next Sunday in church, make a public confession for her offense, and then return to live with her husband. However, Mary’s brother informed the minister that she had left town (and her church) a month and a half earlier. Other records from the church show that Stephen stayed in Lebanon; the church hired him to build a new meetinghouse a few years later. Mary did not return.

Records like these can help us understand responses to church discipline in a period when divorce was unavailable to most women. Communities struggled over their church’s authority to order people’s lives, and sometimes efforts to maintain relationships and covenants failed.

By Tricia Peone, NEHH Project Director

View the Mary Tilden disciplinary case records here.

Above: Photograph of First Congregational Church of Lebanon, Connecticut, WPA c. 1935-1942. Connecticut State Library.

Baptismal records, 1669-1875, Old South Church in Boston, Massachusetts

These two pages of records from the Old South (Third) Church of Boston, Massachusetts, contain the records of sixty-three baptisms that were performed between October 1741 and August 1742. Most entries list a child’s name and their parents’ names, such as “Anna, of Hugh & Mary Vans.” Throughout the eighteenth century, baptizing children of adult church members and children of adults who owned the covenant was a common but immensely significant ritual. Churches were the primary recordkeepers of births and deaths, so these registers have long been essential for genealogists, and the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) digital archive provides unparalleled free access to thousands of pages of baptism and membership lists.

These two pages of records from the Old South (Third) Church of Boston, Massachusetts, contain the records of sixty-three baptisms that were performed between October 1741 and August 1742. Most entries list a child’s name and their parents’ names, such as “Anna, of Hugh & Mary Vans.” Throughout the eighteenth century, baptizing children of adult church members and children of adults who owned the covenant was a common but immensely significant ritual. Churches were the primary recordkeepers of births and deaths, so these registers have long been essential for genealogists, and the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) digital archive provides unparalleled free access to thousands of pages of baptism and membership lists.

With a quick perusal, these records do not appear to be particularly noteworthy. Lists of baptisms, organized by date, are among the most common items contained in the NEHH collections. However, when we read more carefully, we notice that ten (nearly sixteen percent) of the people baptized during these months were of African descent. While Black people were baptized and joined this church throughout the eighteenth century, these two pages mark a particularly large concentration of Black baptisms. Following the revival preaching of George Whitefield and other ministers during 1741 and 1742, unusually large numbers of people joined Old South as full members or by owning the covenant, including a noticeable increase of enslaved Black people. However, Old South’s embrace of revivalism was not the only factor that influenced their participation in churches. All of Boston’s eighteenth-century Congregational and Anglican churches baptized Black people; more than 250 people of African descent were baptized in Boston’s predominantly white churches between 1730 and 1749.

The ten Black people whose names appear on these pages were enslaved when baptized, and only a couple of them ever gained their freedom. Seven people (Scipio, Thomas, Pompey, Flora, Dinah, Lucy, and Katherine) were listed as “servants to” other individuals; “servant” was the contemporary synonym for slave, and some of these people were listed as property in probate records. In some cases, enslaved people do not appear in any other types of records besides New England’s church registries. These seven enslaved people were baptized as adults because each person owned the baptismal covenant for themself. The other three Black people were listed with their parents’ name and without reference to a white enslaver: The baptisms of “Charles, of Scipio;” “Ann, of James & Ann;” and “Katharine, of Cornwall & Katharine” were noted in a way that suggest the parents’ desire for their child’s baptism and a recognition of the parents’ responsibility for their spiritual development. Scipio and Sylvia, who were married by an Old South minister, had seven children, beginning with Charles, baptized at Old South between 1741 and 1759.

While these records do not include the words or details about the day-to-day religious experiences of enslaved people, they are important sources for understanding the connections between race and religion in New England. Collectively, the actions of hundreds of enslaved people – attending services, seeking baptism for themselves and their children, being married by a Congregational minister – serve as witnesses to the lives they sought to build for themselves within the oppressive system of slavery.

By Richard J. Boles, Associate Professor of History at Oklahoma State University

View the Old South baptism records here.

For more information, see NEHH’s Black and Indigenous Research Guide.

Above: Old South Church, Washington Street, 1850. Digital Commonwealth.

Church records, 1629-1843, First Church in Salem, Massachusetts

The church records digitized by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH), along with property and probate records, are some of the most important sources for recovering the stories and lives of colonial-era Black New Englanders.

The church records digitized by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH), along with property and probate records, are some of the most important sources for recovering the stories and lives of colonial-era Black New Englanders.

For several years during the mid-eighteenth century, Pompey Mansfield was elected “King” of the Black community in the Lynn, Massachusetts area. After his enslaver, Thomas Mansfield, was thrown from his horse and died, Pompey gained his freedom and was able to purchase a piece of property. His profession is listed as a clothier, which he practiced alongside members of the Mansfield family. Each year on “Black Election Day,” Pompey entertained the community at his property and celebrated with food, song, dancing, and games.

In a deed dated November 16, 1787, Pompey relinquished his property to the heirs of Isaac Hower, another man of African descent, “in consideration that Isaac Hower late of Salem deceased did in his lifetime furnish me with monies with which I purchased…two acres of land situate in Lynn.” The digitized records of the First Church in Salem provide us with more information about this Isaac Hower and his family: On May 28, 1749, “Isaac Negro of Saml Gardner” was baptized. Several other entries include a daughter, Flora, who was baptized in 1760 and a son named Titus who was baptized in 1765. All were enslaved by Samuel Gardner.

Gardner was a prominent member of the Salem community, owning various properties and mills. He had several business dealings with the Mansfield family, who owned mills in Lynn. It is likely that Pompey and Isaac knew each other through this connection, but how was Isaac able to help Pompey purchase his property? Samuel Gardner died in 1769. In his will, he left to his wife Elizabeth “his Negro Boy Titus (Isaac’s son), as a servant for life” and to Isaac “ten Pounds lawful money … and it is my Will that at my Decease he be and hereby is Manumitted and set free … and If hereafter he be unable to support himself, that he be supported by my sons … so as to free the Town of Salem from any Charge for the support and Maintenance of sd Isaac.” These records reveal the overlapping and interconnected religious and economic lives of white and Black families in New England.

By Diane Fiske, NEHH transcriber, First Parish Church Dover, New Hampshire

View the records of the First Church in Salem here.

Above: View From Saugus River Towards Lynn, undated. Saugus Public Library.

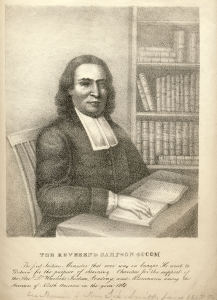

Letter by Jeffrey Smith and Nathaniel Whitaker in support of the Indian school in Connecticut, 1763

This letter soliciting donations from “Christian Friends in Great Britain and Ireland” for the expansion of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, sits on the borders of multiple institutions, archives, and nations. Composed by two influential, Long Island-born Presbyterian ministers who advocated for the “advancement of Christianity among the Benighted Savages of North America,” the missionary intentions of the writers and their condescending perception of Indigenous peoples is apparent. This leads to a series of questions: How did such a perception not only justify, but compel, missionaries and their vast networks of supporters to breach the spiritual, political, and territorial integrity of Indigenous nations? What is the role of charitable institutions within colonization and empire-building projects, especially given that the Indian Charity School did not receive funds directly from government entities (hence the need for donations)? What histories, institutions, and archives need to be brought into conversation with each other to demonstrate such linkages? We might think of the continuities and discontinuities between Harvard College’s 1650 charter stating that the college was established “to conduce to the education of the English and Indian youth of the country” and to the founding of Dartmouth College, the direct heir to the Indian Charity School that did away with the pretense of Indian education altogether. But to ask these questions is to put colonial figures and projects at the center of the inquiry.

This letter soliciting donations from “Christian Friends in Great Britain and Ireland” for the expansion of Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian Charity School in Lebanon, Connecticut, sits on the borders of multiple institutions, archives, and nations. Composed by two influential, Long Island-born Presbyterian ministers who advocated for the “advancement of Christianity among the Benighted Savages of North America,” the missionary intentions of the writers and their condescending perception of Indigenous peoples is apparent. This leads to a series of questions: How did such a perception not only justify, but compel, missionaries and their vast networks of supporters to breach the spiritual, political, and territorial integrity of Indigenous nations? What is the role of charitable institutions within colonization and empire-building projects, especially given that the Indian Charity School did not receive funds directly from government entities (hence the need for donations)? What histories, institutions, and archives need to be brought into conversation with each other to demonstrate such linkages? We might think of the continuities and discontinuities between Harvard College’s 1650 charter stating that the college was established “to conduce to the education of the English and Indian youth of the country” and to the founding of Dartmouth College, the direct heir to the Indian Charity School that did away with the pretense of Indian education altogether. But to ask these questions is to put colonial figures and projects at the center of the inquiry.

What is not as obvious but is even more important for the work of surfacing New England’s Hidden Histories (NEHH) is considering the perspectives, hopes, and actions of Indigenous peoples and nations. What accounts for the stated “fondness of several tribes of the Indians towards the said School”? How might participating Native communities have understood the place of Christianity and colonial-style schooling as elements constituting modern Indigenous nations? What kind of relationships, benefits, and responsibilities did they hope would flow from sending their children to such a school? And, to avoid a wholly instrumental view, we must also contemplate how Native people engaged with colonial institutions and religion in ways that were no less intellectually rigorous or spiritually consequential as their white New England counterparts, and in fact perhaps even more so because these borderlands figures were attempting to reconceptualize and reorient colonial forms toward Indigenous thriving.

One such Native leader whose work goes conspicuously unmentioned in this letter is the Mohegan minister Samson Occom (1723-1792), who was initially the most vocal advocate for Wheelock’s school. Two years later, Occom undertook a fundraising tour across Great Britain and Ireland that realized the financial hopes of this letter beyond Smith and Whitaker’s imaginations. Occom’s prolific, often impassioned writings – particularly his advocacy for Indigenous education and his disappointment and anger when Wheelock reappropriated the funds to establish Dartmouth College, an almost-exclusively white-serving institution – provides one counterpoint to this letter that centers Indigenous desires and priorities. But Occom is only one of a host of Native people whose thoughts and desires impinge upon this letter.

Where might we find the perspectives of the Native women who agreed to send their children to the school and the Native girls who attended? What sources might bear witness to – or at least bear traces of – the “zeal and indefatigable labor” of Indigenous women for the spiritual, intellectual, and political well-being of their children and their nations? When, as per Occom’s autobiography, we consider that it was his mother who established the relationship between her son and Wheelock, might we also discern in this fundraising letter, faint traces of Indigenous women’s visionary power together with their visceral pain in making the consequential decision to send their children to the “remote region” – geographically, nationally, and epistemologically – of the Indian Charity School?

In short, there is a necessary critical reading of this document that helps readers understand its historic colonial force; paradoxically, this letter also compels us to contend with the thoughtful and powerful Indigenous women and men whose lives, labor, and creativity Smith and Whitaker almost completely obscure.

By Anthony M. Trujillo, PhD Candidate, Harvard University, and past recipient of the American Congregational Association - Boston Athenaeum Research Fellowship.

View the letter by Jeffrey Smith and Nathaniel Whitaker here.

Above: Portrait of Samson Occom, c. 1830. Congregational Library & Archives.

Unknown Author, Boston Massacre sermon, circa 1770

On March 5, 1770, British regulars, stationed in Boston, were confronted by a rowdy, snowball-throwing crowd, which resulted in the harassed soldiers firing, killing five, and wounding others. Americans quickly labeled the incident the “Boston Massacre,” which has gone down in our country’s lore as a signal turn in the relationship of Massachusetts, if not that of the North American colonies, with the mother country. Numerous depictions vilifying the redcoats’ actions and conferring on the victims a martyr’s crown quickly issued from the press as broadsides and pamphlets containing narratives, poems, orations, and even an engraving by Paul Revere.

On March 5, 1770, British regulars, stationed in Boston, were confronted by a rowdy, snowball-throwing crowd, which resulted in the harassed soldiers firing, killing five, and wounding others. Americans quickly labeled the incident the “Boston Massacre,” which has gone down in our country’s lore as a signal turn in the relationship of Massachusetts, if not that of the North American colonies, with the mother country. Numerous depictions vilifying the redcoats’ actions and conferring on the victims a martyr’s crown quickly issued from the press as broadsides and pamphlets containing narratives, poems, orations, and even an engraving by Paul Revere.

As word spread in the days following the tragedy, numerous New England ministers, who routinely reported the latest news from the pulpit, delivered sermons—now sadly lost—reflecting on its meaning, some expressing outrage, others counseling calm. One such manuscript sermon, however, has survived in the New England’s Hidden Histories (NEHH) digital archive. It was composed by an unidentified preacher, likely from the Boston area, in the days immediately following the incident. The sermon of twelve octavo-sized leaves is written with a striking immediacy, filled with abbreviations and even shorthand symbols to save time and space. As the text progresses, the writer makes more and more changes, excising words and passages and squeezing in revisions. Different inks bespeak layers of such changes, an effort to strike the right tone.

From his scripture text, Psalm 85:6, in which the Psalmist asks God to “revive us again,” the preacher conjures the traditional identification of the founding generation with the ancient people of Israel. Their “errand” into the wilderness, after persecution at the hands of the English government and church, and exodus across the Atlantic, was blessed by God, who prospered their work to re-establish churches after the example of the earliest Christians. This consideration of the “Fathers” and their “happy success” calls forth a rehearsal of providential historical events from settlement to the Glorious Revolution of 1688. However, when the present generation is compared with the founders, there is much wanting. Employing the tested rhetoric of the Jeremiad, the preacher bemoans the sins and shortcomings of New England’s inhabitants. Yet there is hope for them, if they will but pray to God to revive them, and repent and reform—this is the way to remain a “free and happy” people. Human joy must “terminate” in God; in giving God glory, New England will realize the greatest peace and felicity.

The speaker, horrified by what has happened, couches the violence in the recent series of acts and taxes, implying that this crisis too shall pass, though only after a recognition that all have sinned and share in responsibility. Although the Congregational churches were competing with the Church of England in the colonies, this minister claims that he does not resent any who go over to episcopacy. Also, he denies that the colonies have ever had any idea of “independency.” Not yet, therefore, do we have here a call for rebellion and separation. In a few years, however, if our minister was typical, his pious, conciliatory message would change.

Kenneth P. Minkema, Yale University, founding member of the New England Hidden Histories Project.

View the Boston Massacre sermon here.

Above: Paul Revere, The bloody massacre perpetrated in King-Street Boston, c. 1770. Boston Public Library.

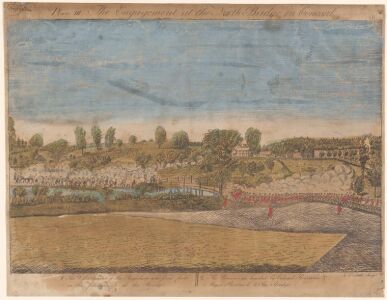

Collected prayer requests, undated, First Congregational Church in Medfield, Massachusetts

This small slip of paper bears a 44-word prayer in which Israel Heald (1736–1815), a Minuteman from Acton, Massachusetts, thanked God for “Covering his head in the Day of battel” and returning him safely home to his family and friends. For nearly two centuries, parishioners in Congregational churches across New England submitted similar prayer notes—or prayer bills as they were called—to their ministers each week. Tacked to meetinghouse doors or deposited in special boxes, the prayers were collected and read aloud during Sabbath meetings. Most of the roughly 200 surviving examples were preserved by ministers, such as Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards, who scavenged them as scrap paper for sermon notes or drafts of letters.

This small slip of paper bears a 44-word prayer in which Israel Heald (1736–1815), a Minuteman from Acton, Massachusetts, thanked God for “Covering his head in the Day of battel” and returning him safely home to his family and friends. For nearly two centuries, parishioners in Congregational churches across New England submitted similar prayer notes—or prayer bills as they were called—to their ministers each week. Tacked to meetinghouse doors or deposited in special boxes, the prayers were collected and read aloud during Sabbath meetings. Most of the roughly 200 surviving examples were preserved by ministers, such as Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards, who scavenged them as scrap paper for sermon notes or drafts of letters.

Congregational prayer bills typically fall into one of several categories: prayers sanctifying the death of a loved one; petitionary prayers beseeching God for aid in moments of danger; and prayers of thanksgiving for divine mercy during moments of illness, childbirth, or, in Heald’s case, warfare. Heald’s prayer bill is unique. It is one of the few notes related to the events of the American Revolution.

Son of a prominent town leader and church deacon, Israel Heald married Susannah Robbins (1738–1822) of Chelmsford in 1760. They settled on a farm near the border of Westford and raised a family of six children. Responding to the Acton Alarm on April 19, 1775, Heald marched to Concord and engaged the British at the North Bridge. Several months later, he helped secure Dorchester Heights during the siege of Boston. On October 28, 1776, Hessian forces overran Heald’s company on Chatterton’s Hill during the devastating Battle of White Plains. He likely wrote this prayer bill shortly after returning home to convalesce from wounds sustained during the engagement.

The Heald manuscript is one of fifteen prayer bills discovered among a set of loose church papers at the Medfield Historical Society and digitized by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH). Eleven of these precious manuscripts address the hopes and fears of Massachusetts families whose men served in the militia or Continental Army. Several were composed by Heald’s neighbors in Acton, and his wife wrote one prior to the Battle of White Plains. The Medfield prayer bill collection provides a rare glimpse into the day-to-day religious lives of lay men and women during the tumultuous early years of the American Revolution.

Douglas L. Winiarski, professor of religious studies at the University of Richmond, founding member of the New England Hidden Histories Project.

View the Israel Heald prayer bill here.

Above: Amos Doolittle after Ralph Earl, Plate III. The Engagement at the North Bridge in Concord, 1775. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library.

Hartford South Association records, 1743-1822

In eighteenth-century Congregationalism, ministerial associations provided regional stability and cohesion. Regional associations examined ministerial candidates, licensed preachers, and mediated disputes. Association meetings also provided nearby ministers a chance to build friendships and camaraderie. The Hartford South Association left the most complete eighteenth-century record book of any association in the Connecticut Valley, and the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) made this valuable source of information more accessible by digitizing it. Even during the American Revolution, many of its wartime meeting minutes were recorded. These records reveal the persistence of longstanding disputes in Congregationalism, even during wartime.

In eighteenth-century Congregationalism, ministerial associations provided regional stability and cohesion. Regional associations examined ministerial candidates, licensed preachers, and mediated disputes. Association meetings also provided nearby ministers a chance to build friendships and camaraderie. The Hartford South Association left the most complete eighteenth-century record book of any association in the Connecticut Valley, and the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) made this valuable source of information more accessible by digitizing it. Even during the American Revolution, many of its wartime meeting minutes were recorded. These records reveal the persistence of longstanding disputes in Congregationalism, even during wartime.

One such persistent debate was over eligibility for baptism. This debate prompted the Halfway Covenant of the 1660s but was still a pressing concern for the Congregational church in Chatham, Connecticut in 1781. The minutes from the Hartford South Association meeting on June 5, 1781, record the Chatham dispute:

A petition from Chatham, signed by sundry persons, church members and others under the pastoral care of the Rev. Cyprian Strong (1743-1811), was preferred to this Association requesting advice respecting some difficulties subsisting among them in the church and society of Chatham, with regard to the Rev. Mr. Strong's administration of baptism; particularly in his withholding baptism from children, neither of whose parents come to the ordinance of the Lord’s Supper.

Some of Chatham’s regular church attendees had not become full members and communicants yet, not through mere neglect, but out of a deep fear of partaking in the Lord’s Supper unworthily. These parishioners wanted to present their children for baptism by owning the church covenant, but Rev. Strong opposed this practice. He was concerned that these people might be unconverted and that their children should not, therefore, be baptized.

The Hartford South Association mediated a compromise between the minister and his congregants, appointing a committee to look into the matter. The committee recommended that the parents in question be allowed to have a neighboring minister baptize their children after owning the covenant. But the committee carefully specified that church members who elected to take their children to another minister for baptism were still under the ecclesiastical authority of Rev. Strong in every other respect. The compromise was successful. Rev. Strong remained the pastor to the church in Chatham as well as a faithful member of the association. While such a recommendation did not take away the basic disagreement, it did preserve ecclesiastical harmony, a key priority for regional ministerial associations in the eighteenth century.

Christopher Walton, PhD Candidate, Southern Methodist University, and past recipient of the American Congregational Association - Boston Athenaeum Research Fellowship.

View the Hartford South Association records here.

Above: Photograph of the Congregational Church of East Hampton (formerly Chatham), Connecticut. John Phelan, Wikimedia Commons.

Letter from Betsy Flagg to Ward Cotton, 1812 June 18

In language as simple and straightforward as her penmanship, Betsy Flagg (1787-1827) reminds the minister of the First Congregational Church in Boylston, Massachusetts, of her request for dismission to the Church of Christ in neighboring Worcester in June 1812. Another note, written a little over a month later, makes the request once again. Reading between the lines, it is not hard to imagine Flagg’s rising frustration. Yet, both letters close with the same ostensibly warm, “I remain your friend.”

In language as simple and straightforward as her penmanship, Betsy Flagg (1787-1827) reminds the minister of the First Congregational Church in Boylston, Massachusetts, of her request for dismission to the Church of Christ in neighboring Worcester in June 1812. Another note, written a little over a month later, makes the request once again. Reading between the lines, it is not hard to imagine Flagg’s rising frustration. Yet, both letters close with the same ostensibly warm, “I remain your friend.”

While less than one hundred words in Betsy Flagg’s hand survive in the New England’s Hidden Histories (NEHH) digital archive, thousands of words written about her can be found, digitized and transcribed. The documents come from multiple hands and archival collections, reunited after two centuries on NEHH’s digital platform. Rev. Ward Cotton of the Boylston church, Rev. Dr. Samuel Austin of the Worcester church, and even the Worcester Association of Congregational Ministers all weighed in on the merits of dismissing Flagg from one church to another. They, too, strove to remain friendly in their dialogue, although the strain is not difficult to perceive.

Precipitating this correspondence was Flagg’s expression of concern about the spiritual health of her minister and fellow congregants. This led her to decide to stop taking communion as a result. The Boylston church’s judgment of censure and suspension for what they saw as “[h]abitual neglect of the ordinances of the Gospel in this place, aggravated by reviling, & slanderous language, & unchristian behaviour towards the Pastor & the Church” led her to seek a new church community. When the neighboring church in Worcester allowed her to take “occasional” communion with them, they were accused of going against the Cambridge Platform, still revered as a model centuries later.

Betsy Flagg’s case touched some of the fundamental questions facing nineteenth-century Congregationalism: the right of the individual church member to dissent, the threat inherent in withdrawing from the sacraments, the meaning of discipline, the limits of civility, and the boundaries of authority. And at the base of it all, a contest over who could claim to be a “real Gospel Church.” In the face of evangelical revivalism and the looming tension between orthodox and liberal wings of the church, Congregationalists would see this come to a head with the Unitarian schism a decade later.

NEHH reminds us that young women from Central Massachusetts were just as invested in contests over religious belief and practice as the most erudite ministers of Boston, Cambridge, and Hartford, upon whom historians have lavished far more attention, Perhaps we can heed Betsy Flagg’s request and wait no longer to recover their stories.

Kyle Roberts, Executive Director, Congregational Library & Archives

View Betsy Flagg's letter to Ward Cotton here.

Above: Boylston Church from Centennial celebration of the incorporation of the town of Boylston, Massachusetts, August 18, 1886, Worcester: Sanford & Davis, 1887.

Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society records, 1834-1846

In the 1630s, enslaved Africans began to arrive in the Massachusetts Bay Colony on ships owned by men from Salem. Although consistent petitions by enslaved people led the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to rule in 1783 that slavery was incompatible with the state’s constitution, slavery ended in Massachusetts via a process of gradual erosion. The 1790 census records indicate that no one in Massachusetts held people as property in their homes, but Salem’s captains did not discard their ships. Some of them continued to traffic enslaved people throughout the Atlantic World. Nineteenth-century Salem was home to notorious slave-traders and leading Black anti-slavery activists.

In the 1630s, enslaved Africans began to arrive in the Massachusetts Bay Colony on ships owned by men from Salem. Although consistent petitions by enslaved people led the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court to rule in 1783 that slavery was incompatible with the state’s constitution, slavery ended in Massachusetts via a process of gradual erosion. The 1790 census records indicate that no one in Massachusetts held people as property in their homes, but Salem’s captains did not discard their ships. Some of them continued to traffic enslaved people throughout the Atlantic World. Nineteenth-century Salem was home to notorious slave-traders and leading Black anti-slavery activists.

Women of color in Salem formed the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society on February 22, 1832. By the 1830s, women were leading abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic, but their male counterparts disagreed about the question of women’s leadership. Therefore, abolitionist women created Female Anti-Slavery Societies and described their efforts as an extension of their duties as Christian women. The roughly fifty members of the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society determined that “as moral and responsible beings as those upon whom the law of love given in the Sacred Scriptures is binding - they are obligated to lend their individual and united influence . . . in favour [sic] of immediate emancipation.”

In 1834, the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society became an interracial group in which women of color continued to hold leadership roles. These women of color leaders included Clarissa C. Lawrence, who served in numerous leadership roles within the Society, and Susan H., Caroline, and Maritchie Remond. The Remond patriarch, John Remond (1788-1874), had arrived on Massachusetts’s North Shore in 1798. By 1800 he joined the community of about 300 free Black people living in Salem. The Remonds were committed to immediate abolition, aiding fugitives from Southern slavery, and improving the educational opportunities available to Black children in Massachusetts. The digitization of these rare records by the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) helps reveal the activism of these women, who were part of a community of nineteenth-century Black abolitionists in Salem and beyond. Together, they advocated relentlessly for the cause of freedom.

Jaimie D. Crumley, Assistant Professor of Gender Studies and Ethnic Studies, The University of Utah

View the Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society records here.

Above: Portrait of Sarah Parker Remond (1824-1894), undated. Massachusetts Historical Society.

Conclusion

These thirteen stories from communities throughout New England are drawn from primary source materials dispersed across many libraries, archives, and church basements. Over the past twenty years, the New England’s Hidden Histories project (NEHH) has brought these sources together in a freely accessible digital archive.

By providing access to these records through digitization and transcription, NEHH shares resources with communities and partner institutions. NEHH serves a large and diverse audience, which includes middle, high school, and college students; educators; genealogists; researchers from churches, universities, and local historical societies; and independent scholars.

From this unparalleled collection of records, exciting new histories are being written that challenge us to re-examine our understanding of early New England. The thirteen essays in NEHH@20: Re-Examining Stories from New England Communities reveal some of the remarkable ways that these records can be used to tell community stories. The following page has a list of books and articles that demonstrate some of the important body of work that has developed from the NEHH project.

In the coming years, NEHH will continue to grow and add new materials to the digital archive. What new stories will you uncover by volunteering to transcribe records or using the NEHH digital archive for teaching or research?

Opposite pane: This map illustrates the locations and types of records available through New England’s Hidden Histories and the locations of our partner institutions.

Further Reading

Beales, Jr., Ross. “‘To Promote Civility and Benevolence’: Rev. Ebenezer Parkman and an Acadian Refugee Family (1750s).” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 51, no. 1 (Winter 2023): 66-89.

Bendroth, Peggy. “New England's Hidden Histories: Congregational Church Records in the Digital Age.” Bunyan Studies 20 (2016): 111-9.

Boeddeker, Hannah, and Kelly Minot McCay, editors. New Approaches to Shorthand: Studies of a Writing Technology. Berlin: De Gruyter. 2024.

Boles, Richard. Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Segregated Churches in the Early American North. New York: New York University Press. 2020.

Carté, Katherine. Religion and the American Revolution: An Imperial History. Williamsburg, VA: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 2021.

Coffey, John. The Oxford History of Protestant Dissenting Traditions, Volume I, The Post-Reformation Era, 1559-1689. New York: Oxford University Press. 2020.

Cooper, James F. Tenacious of their Liberties: The Congregationalists in Colonial Massachusetts. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

-----“New England's Hidden Histories: Church Records and Church Practice in Colonial New England.” Bunyan Studies 20 (2016): 120-133.

Couch, Daniel Diez, and Matthew Pethers, editors, The Part and the Whole in Early American Literature, Print Culture, and Art. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press. 2024.

Dickson-Smith, Susan E. “‘For Truth and Right:’ Rev. Amos Noë Freeman and Portland, Maine’s Abyssinian Church, 1826 to 1917.” M.A. Thesis. University of Maine. August 2024.

Duclos-Orsello, Elizabeth. “The Fullness of Enslaved Black Lives as Seen through Early Massachusetts Vital Records.” Genealogy 6, no. 1(2022): 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy6010011

Minkema, Kenneth, and James F. Cooper, Jr. The Colonial Church Records of the First Church of Wakefield (Reading) and the First Church of Rumney Marsh (Revere), Massachusetts. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts. 2006.

----- The Sermon Notebook of Samuel Parris, 1689-1694. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts. 1994.

Neele, Adriaan C. Before Jonathan Edwards: Sources of New England Theology. New York: Oxford University Press. 2018.

Richardson, Kaitlyn. “The Becket Family of Salem, Massachusetts.” The Thetean: A Student Journal for Scholarly Historical Writing, 51, no. 1 (2022).

Rogers-Stokes, Lori. Records of Trial from Thomas Shepard’s Church in Cambridge, 1638–49: Heroic Souls. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. 2020.

Tipson, Baird. Inward Baptism: The Theological Origins of Evangelicalism. New York: Oxford University Press. 2020.

Winiarski, Douglas. Darkness Falls on the Land of Light: Experiencing Religious Awakenings in Eighteenth-Century New England. Chapel Hill, NC: Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, VA, by the University of North Carolina Press. 2017.

Winship, Michael. “Hidden in Plain Sight: John Cotton’s Middle Way and the Making of the Cambridge Platform of Church Discipline.” Church History 91, no. 4 (December 2022): 780-802. doi:10.1017/S0009640722002785.

Acknowledgements

NEHH@20: Re-Examining Stories from New England Communities was curated by Richard Boles and Tricia Peone. The digital exhibition was designed by Zachary Bodnar. Graphics for the exhibition were created by Lauren Hibbert.

This exhibition is dedicated to Hal Worthley, whose work inspired the NEHH project. Watch a video of Hal describing his inventory project here.

Special thanks to the exhibition contributors:

Richard Boles

Jaimie Crumley

Diane Fiske

Helen K. Gelinas

Samuel Jennings

Ken Minkema

Tricia Peone

Kyle Roberts

Lori Rogers-Stokes

Anthony Trujillo

Christopher Walton

Doug Winiarski

Barbara Worthley

Special thanks also to NEHH partner institutions whose materials appear in this exhibition:

American Ancestors (formerly New England Historic Genealogical Society)

American Antiquarian Society

Connecticut Museum of History and Culture (formerly the Connecticut Historical Society)

The Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum

New England’s Hidden Histories has received generous support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Council on Library and Information Resources, and ATLA.